‘Team God’

The doctrine of the Trinity states that God is ‘One in three persons’, but that should not lead us to think there are three gods, or even three parts of God, operating independently from one another, for God is one in a most perfect unity.

Nowhere in the New Testament, the earliest Christian witnesses we have, is there a statement of this doctrine, or the simple formula, ‘three persons One God’. But there are passages in the New Testament where three ‘persons’, the Father God, Jesus Christ, the Holy Spirit, are entwined together in a living way. Then we can see all three are united in the ‘Team God’ playing the real serious game of doing something good with human beings. This team is not like a football team that is trying to beat another team (united against others). It is more like the team in a hospital operating theatre, working together, to bring the patient back to healthy life.

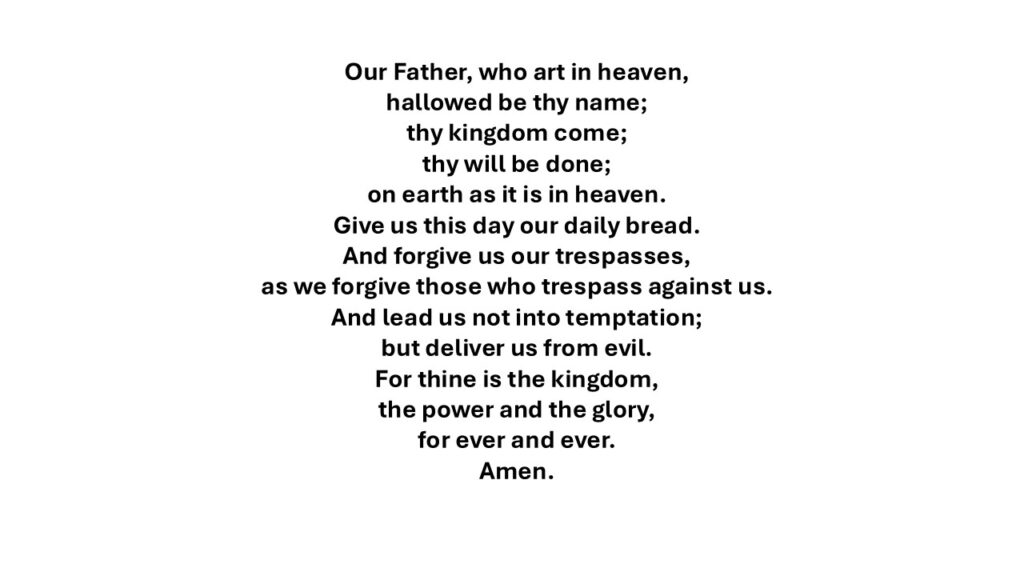

One place where we see this team at work is in Romans 5.1-5. Therefore, since we have been justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ. 2 Through him we have also obtained access by faith into this grace in which we stand, and we rejoice] in hope of the glory of God. 3 Not only that, but we rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, 4 and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, 5 and hope does not put us to shame, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us.

We have peace with God: that is in Paul’s view a great and surprising gift, for he has spent the earlier chapters showing that ‘all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God’ and earning the wages of sin which is death. God created human beings in his image, so that they would display the glory of God as they live in the earth – God called human beings to walk in his ways, and to be a blessing to the world, as they are blessed. But it has not turned out like that. Look at the world, our nation, our selves, we cannot say, complacently, that we image God and reflect his glory.

Peace with God is not to be assumed. Yet God makes peace with enemies, through our Lord Jesus Christ… who died for us.

Why do this great work of peacemaking through Jesus Christ? Why not do it by a simple direct act of divine power and authority? After all, God is free and able to do anything he likes, isn’t he? And God is loving, isn’t he? Why shouldn’t God simply declare ‘I love you: you are accepted’.

One reason why God does not take this quick and easy way is that it would be unrealistic and one-sided. God will not save human beings from their sin without taking their sin seriously. Sin is a great tangle of human failure that has to be untangled, worked through in detail, not cut at a stroke. God wants the string straightened out so that it can be used again for good. The mess of human being has to be repaired from within human being. To do otherwise would be a mere cosmetic job, a superficial con. It would be as shoddy as putting a new coat of smart glossy paint on a rotten piece of wood, to spare ourselves the pain of chisel and saw.

So God becomes human and dwells among us. God in Jesus lives humanly, with all the toil that involved; he suffers under the mess, struggles against it as he finds it in the people he encounters. Jesus lives in faithfulness to God despite all the difficulties, and only so is humanity being remade by God from inside the mess, working through the realities of human living and dying.

In Jesus Christ, we see and are drawn into God’s great costly work of renewing humanity in truth and love. It takes time and trouble, which God is involved in. So through Jesus Christ, we have access to the grace, the good favour of God, in which we stand, and then we can boast, not in our own strength or achievement, but in the hope of sharing the glory, not of ourselves, but of God. And because it is through Jesus Christ, we can’t avoid sufferings, but we can also ‘boast of our sufferings’. Jesus suffered, we know. When God does good to us, through Jesus Christ, God calls us to live our human lives as he lived his, not shrinking from the suffering involved in being faithful to the call of God. And as we walk with Jesus, we cannot exempt ourselves from sharing his suffering in some measure.

And yet, says Paul, we can boast of sufferings – how is that? The short answer Paul gives is that through this life-development of endurance and character- formation, hope arises. Long before we come to the final escape from all suffering, to the place where there is no more crying, no more tears, suffering in the way of Jesus produces endurance, and then character, and out of that hope.

Hope is fragile in this world of hostility, insecurity, futility. We hope and are often disappointed. So we learn to be realistic and not expect too much of life, and that is at least prudent. But if that is all there is, it falls short of what God wills. Along the way of life with Jesus Christ, sharing his suffering, a kind of hope is given that does ‘not disappoint because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given us’. Our human hopes are often fragile. We often hope and end up with disappointment.

Disappointment is an aspect of the suffering in our messed up world. But when we have peace with God, when we live by faith in God and not in ourselves, when we share a common life with Jesus Christ, then the love of God is poured in our hearts. And this is not a matter of our moods, but of the Holy Spirit who is given to us – God the Spirit coming close to our spirits, God finding us in the depths. In the last resort, it is not success that saves us from being disappointed, but it is love. And our weak love needs to be called forth and resourced by God who is love, whose Spirit inspires it generously.

This is how Paul gives us God, Jesus Christ, Holy Spirit, working as a team in an effective operation to rescue human being. God, Father, Son and Spirit, involves human beings in the operation of salvation: it is done with us, not merely to us. It’s the kind of operation that is done without anaesthetic, because it recovers and rebuilds human beings in a genuinely human way – which always has to be with human beings, involving them in the doing as well as the receiving. We don’t have a formulaic Trinity here, but the living God in God’s fullness.

Another way into Trinity: John 16.12-17

I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now.13 However, when He, the Spirit of truth, has come, He will guide you into all truth; for He will not speak on His own authority, but whatever He hears He will speak; and He will tell you things to come. 14 He will

glorify Me, for He will take of what is Mine and declare it to you. 15 All things that the Father has are Mine. Therefore I said that He will take of Mine and declare it to you. “A little while, and you will not see Me; and again a little while, and you will see Me, because I go to the Father. 17 Then some of His disciples said among themselves, What is this that He says to us, ‘A little while, and you will not see Me; and again a little while, and you will see Me’; and, ‘because I go to the Father’?

All the Gospels show that Jesus lived an ordinary human life, and was known socially as an ordinary member of society, son of the carpenter of Nazareth. And then Jesus surprised them: he healed the sick, calmed the storm, fed the crowds, so that they asked, what sort of man is this? We are faced with someone unusual. Who is he really?

Jesus taught with authority, so they asked: Where did he get all this insight, this practical wisdom, this soaring vision? Jesus responded unconventionally to poor, to marginal and despised people, he proclaimed good news to the poor, and told and showed broken sinners that they were forgiven. And then some asked, Who is this who forgives sins? Only God can forgive sins. Who is this Son of Man who exercises authority on earth to forgive sins? He blasphemes and blasphemers deserve to die.

But others, the poor and blind and penitent who benefited from him, accepted all this as the gift of God, the sign of God’s living presence, for them. God is with him, they said. He is from God. He does God’s work. He is clearly in God’s team. Meeting him, we meet God. When he talks with us, our hearts burn within us. Shall we go to anyone else? He has the word of eternal life and we have come to believe and know that he is the Holy One of God.

In his Gospel, John, more clearly than the other Evangelists, gives us a picture where the difference between God the Father and Jesus becomes paper thin: I and the Father are one, says Jesus. And yet the difference is plain: God the Father is in heaven, Jesus the Son is on earth. No one has ever seen God, human eyes haven’t got the wavelength, but Jesus is visible. God is eternal, immortal; Jesus the Son has his beginning and his end. Jesus talks about his ‘going away’, as his allotted time comes to an end, and he will leave the disciples. Jesus accepted that limit: he had his day, when the light was shining, and so he could do the work given him to do, but he knew the night was coming when work had to stop.

When Jesus died on the cross, he cried It is finished. He had done his work, in his time; he was finished. But it does not mean God was finished. Jesus said to his disciples, I am going to leave you and you are sad – but don’t be inconsolable: I will send you another Comforter, the Spirit of truth: he will take what is mine and declare it to you. You will lose my human presence on earth, you won’t see me any more, but I will come to you in the Spirit.

So we have another picture of the Trinity team in operation. All that the Father has, has been given to the Son, and the Spirit will take all that belongs to Jesus the Son, all that comes from the Father, and will share it with you. It won’t be shared with disciples for their exclusive benefit, to make them individually a more happy, or balanced, or successful persons. God does nothing to help us in the competitions of life, the quest to be great or the greatest, in this or that way.

Jesus said, If my life went on forever as my own personal life, so that my beautiful being was preserved in its health and prosperity and its gladness about itself, it would be godless, alone and useless. It would be futile, like a seed that was never put in the soil. But Jesus said, a seed should be put in the soil, hidden away in the dark dampness, so that it will die: for if it dies it bears much fruit.

That takes us to the heart of the unbearable reality of God as we see God in Jesus Christ: the God who loves and gives Godself for the life of the world. And when the Holy Spirit shares all that God has, all that God is in Godself, we are not offered blessings and powers which enhance our individuality. We are called insistently, every day, into the way of Jesus, the seed full of the life of God, that falls into the ground and dies.

That was the way Jesus went. The Son who was one with the Father lived his humanity right into the separation of death, and out of that has come much fruit. The Spirit which is free as the wind, that is free to go anywhere, comes to places and to times that Jesus could not reach. All through the world, long after the day of Jesus on earth ended, the Spirit shares the life of Father and Son with human beings.

Jesus brought us God in a living human person, intensely local, in a limited moment. The power of life was packed into that littleness, like a seed. The Spirit is God bursting out like the blossom and fruit that comes from a seed that dies. So much from one little seed: the Spirit in the world from the Son and the Father.

This is the story of God in action, a team of three, each playing its part, together making a more perfect unity than we can get our minds around. It is the story still being made by God, involving human beings all the way.